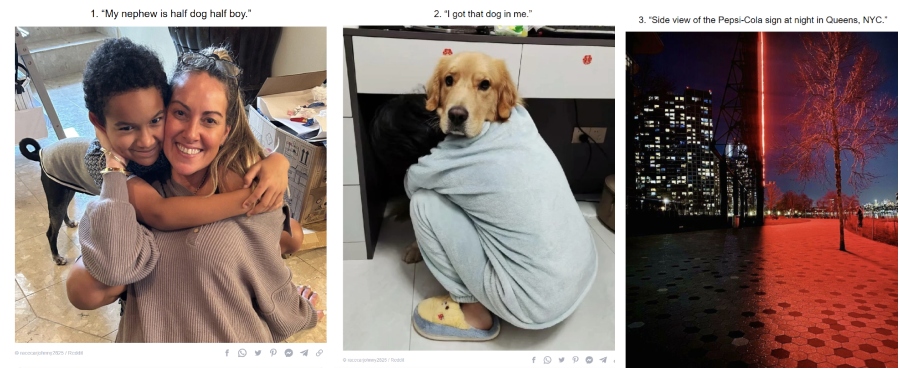

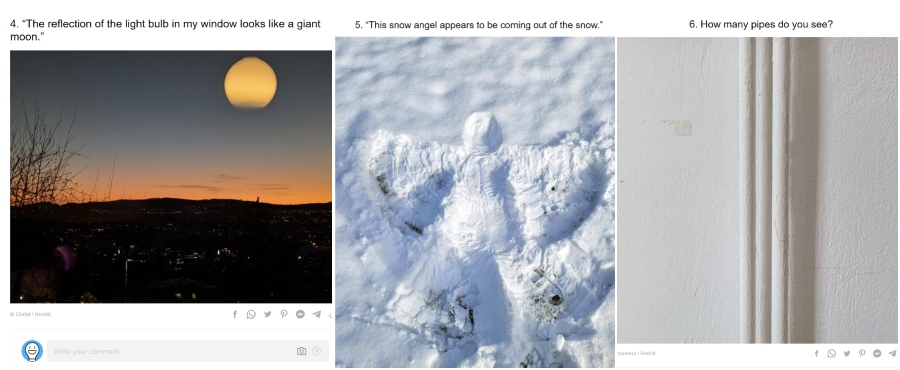

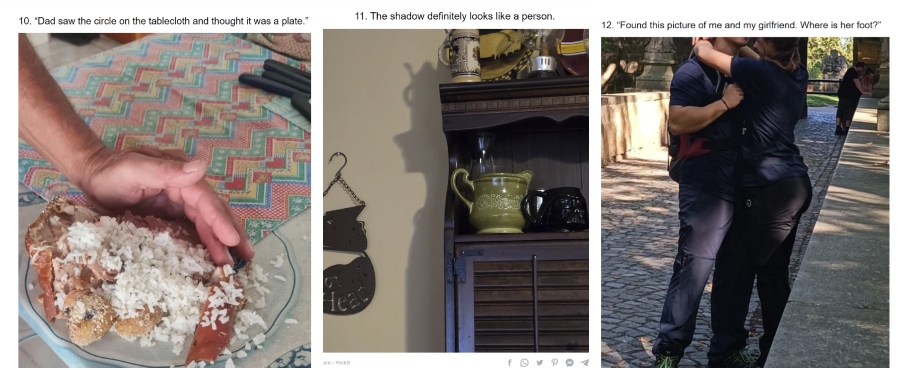

The text explores how ordinary objects can become visually confusing or surprising when viewed from unusual angles or under specific lighting conditions. What feels at first like the brain “playing tricks” is actually the result of incomplete visual information: the viewer is receiving only a fragment of a scene, leading the mind to make quick assumptions based on patterns, habits, and past experience. Photographers who capture these perceptual illusions provide a glimpse into how easily our understanding of the world can shift. By presenting familiar objects in unfamiliar ways, they reveal how fragile and selective our visual interpretation can be. The moment when a mundane environment unexpectedly looks unfamiliar serves as a reminder that perception depends as much on context as on the objects themselves. This interplay between expectation and reality lies at the heart of every accidental optical illusion.

o

A central idea in the text is that our brains constantly attempt to resolve ambiguity, filling in missing information with assumptions drawn from experience. This mental shortcut usually helps us navigate the world efficiently, but it also leaves us vulnerable to misinterpretation when the visual cues are incomplete or misleading. A person in front of a billboard may seem to float, not because anything supernatural is happening, but because the brain inadvertently merges two unrelated layers into one. A tiny object placed close to a camera may appear enormous when the background lacks scale markers. These puzzles highlight how perception is never passive; it is an active process of interpretation, correction, and guesswork. By confronting these illusions, viewers gain insight into the invisible mental processes that govern how they understand what their eyes present to them.

The text also discusses the pleasurable confusion that arises when an image challenges our expectations. Some photographs force viewers to stop and examine what they are seeing, prompting a second, more careful look. A dress that appears torn may turn out to be covered in a shadow shaped by branches overhead. What looks like falling rain might instead be droplets on a windowpane distorting the scene behind it. These instances create a moment of narrative tension: first, the viewer experiences confusion; then comes the revelation that the mind’s initial interpretation was incorrect. The satisfaction of recognizing the real explanation underscores how much enjoyment people find in small perceptual twists. These illusions are not merely visual tricks—they evoke curiosity, engagement, and a sense of wonder at the surprising flexibility of perception.

The act of sharing such photographs becomes an invitation to participate in a broader game of observation. Photographers who publish these illusions are not simply showcasing clever compositions; they are encouraging viewers to question their assumptions and to examine details they might normally ignore. This practice cultivates a more attentive way of looking at the world. Once someone becomes aware of how frequently minor coincidences produce major perceptual distortions, they begin noticing similar phenomena in everyday environments: misaligned shadows, reflections that mimic objects, overlapping shapes that seem fused, or moments when natural lighting alters the proportions of familiar structures. What initially seemed like rare oddities turn out to be surprisingly common—hidden in plain sight until one learns how to look for them. This shift in awareness transforms ordinary scenes into potential sources of intrigue.

The concluding idea is that these moments of misperception are not failures of vision but opportunities for reflection. When something looks strange or out of place, the immediate reaction may be confusion, but that confusion signals a deeper truth: the brain is improvising, constructing a story based on incomplete data. By pausing and reconsidering, we learn to appreciate the limitations and strengths of our perceptual systems. The illusions underscore the importance of perspective—how the meaning of a scene can change dramatically with just a slight shift in position or context. Ultimately, these perceptual tricks encourage humility and curiosity. They remind us that seeing is not the same as understanding, and that the world contains layers of complexity waiting to be uncovered by anyone willing to slow down and look again.